Verve’s Roman Stikkelorum argues that while brand archetypes and the golden circle have a strategic role to play, it may not be the one you think.

I found myself involved in a post dinner chat with friends recently, which verged (as late night discussions sometimes do), onto the topic of astrology. You’ve probably had this conversation yourself. It’s the one where everybody starts off as mocking and sceptical, then somebody (who for whatever reason knows this stuff), starts to reel off the various qualities of star-signs and folks begin to lean in: “actually that is kind of uncanny”…

There’s something endearing to me about how susceptible we are to this stuff. We humans like to think of ourselves as such rational creatures. And yet the attraction of simple, metaphysical explanations for otherwise baffling or complex phenomena is so strong, it seems to get us every time.

It set me thinking about brand archetypes. As with any concept upon which peoples’ careers depend, it’s a topic of heated debate. On one side are the sceptics, chief among them the inimitable Mark Ritson, who lists archetypes in his ‘Top Ten of Marketing Bullsh*t’. On the other: the advocates, like Unilever-VP Deepak Subramanian, who found himself on the wrong end of a Twitter takedown by none other than data-prophet Byron Sharp when he extolled their virtues.

For those who preach the primacy of measurement – step forward Les Binet, Peter Field, Jenni Romaniuk as well as the godfather, Byron – it’s understandable to insist that a (somewhat discredited) Jungian personality model from the world of psychology is an imperfect basis for decision-making. And they have a point. But it's no less reasonable to argue that the fact something resists scientific explanation, doesn’t mean it can't work (the placebo effect is just one such example).

It's true that with enough data from enough people you can reliably predict human behaviour. But there’s one thing the numbers can’t account for: the way a brand makes a person feel.

When in 2001 the authors Margaret Mark and Carol S. Pearson introduced Jung’s archetypes to the marketing world in their book, ‘The Hero and Outlaw’, they described their aims as ‘to provide choices in positioning and branding with a sense of unity and strength’. Or to put it another way: to drive consensus and make brand guardians feel good about the decisions they make – not, notably to form the foundation for the strategy itself.

This is certainly borne out by my experience. At Verve we find archetypes to be a powerful contributor to the process of building a sense of unity among stakeholders. Without this shared belief it doesn't matter how good your strategy is; the people tasked with implementing it will lack the necessary commitment and singleness of purpose to see it through.

And that’s the point. Brand archetypes are about character, not substance. When Mark Ritson pulls the concept to pieces – with his customary energy and humour – he describes a scenario where, instead of relying on data and analysis you ‘come up with the jester and the sage, and you’re kind of done’.

This points to a common misconception. It would indeed be foolhardy to base an entire brand strategy on the identification of an archetype. Nevertheless an archetype can deliver the clarity and momentum necessary to ensure the strategy actually gets executed. In summary it can:

A. Help you get the nuanced information you need out of your client

B. Help you formulate a brand personality

Just like the horoscope-sceptic reluctantly recognising traits that align with their star sign, we all have a strong, shared sense of the values and behaviours attributable to a particular archetype. They’re universal for a reason.

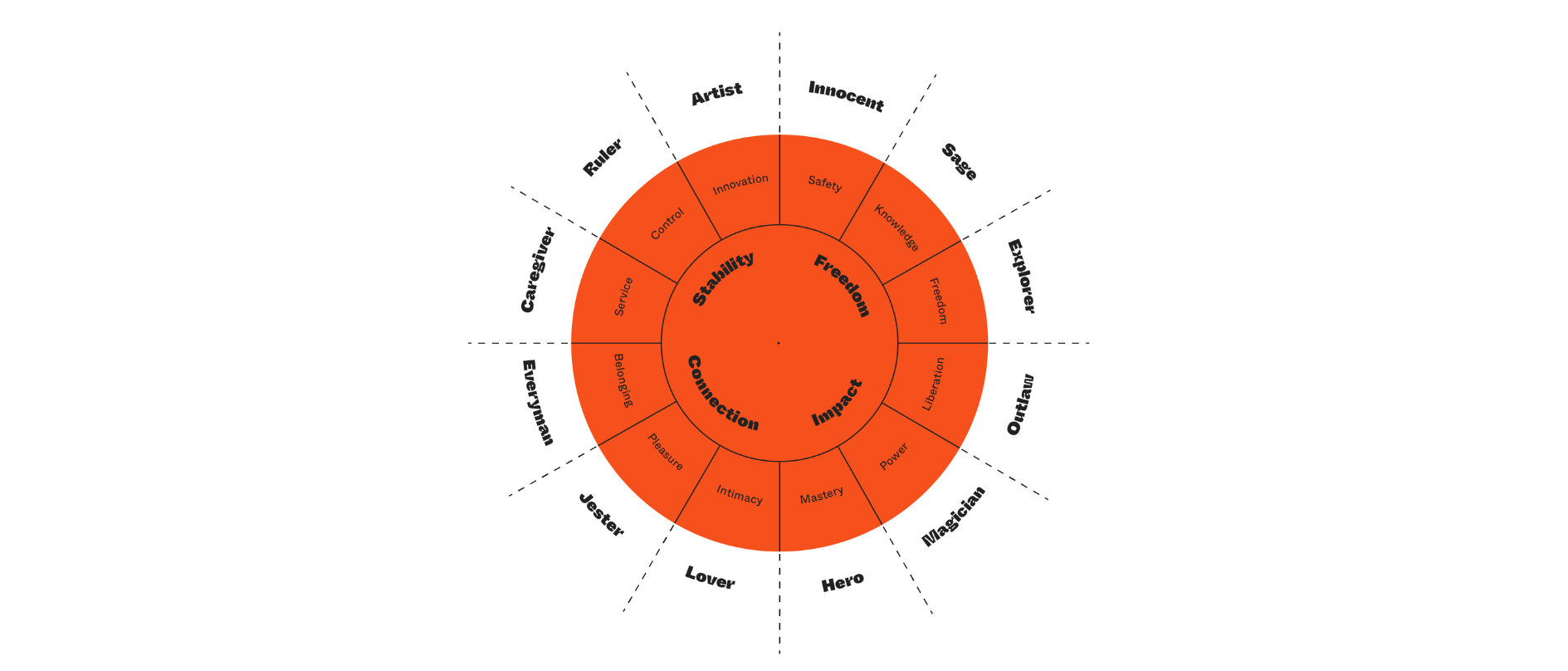

Mark and Pearson organise their twelve archetypes between axes of social vs. selfish and liberated vs. compliant. The fact that that studies have proven these to be both a popular and powerful marketing tool is a reflection of the fact they enable us to assign human attributes to non-human things; to anthropomorphise, and to develop coherence around what may be a diverse agglomeration of products, services, competencies and cultures.

As one weapon in the diverse arsenal demanded in what I call the ‘post digital’ world of brand-building (which is to say, a world where meaningful distinctions between digital and non-digital communication have ceased to exist), the brand archetype fits comfortably into Netherland's marketing guru Giep Franzen's monumental thesis, The Science and Art of Branding. It’s not a question of numbers vs. myth-making. It’s a question of effectively combining the two.

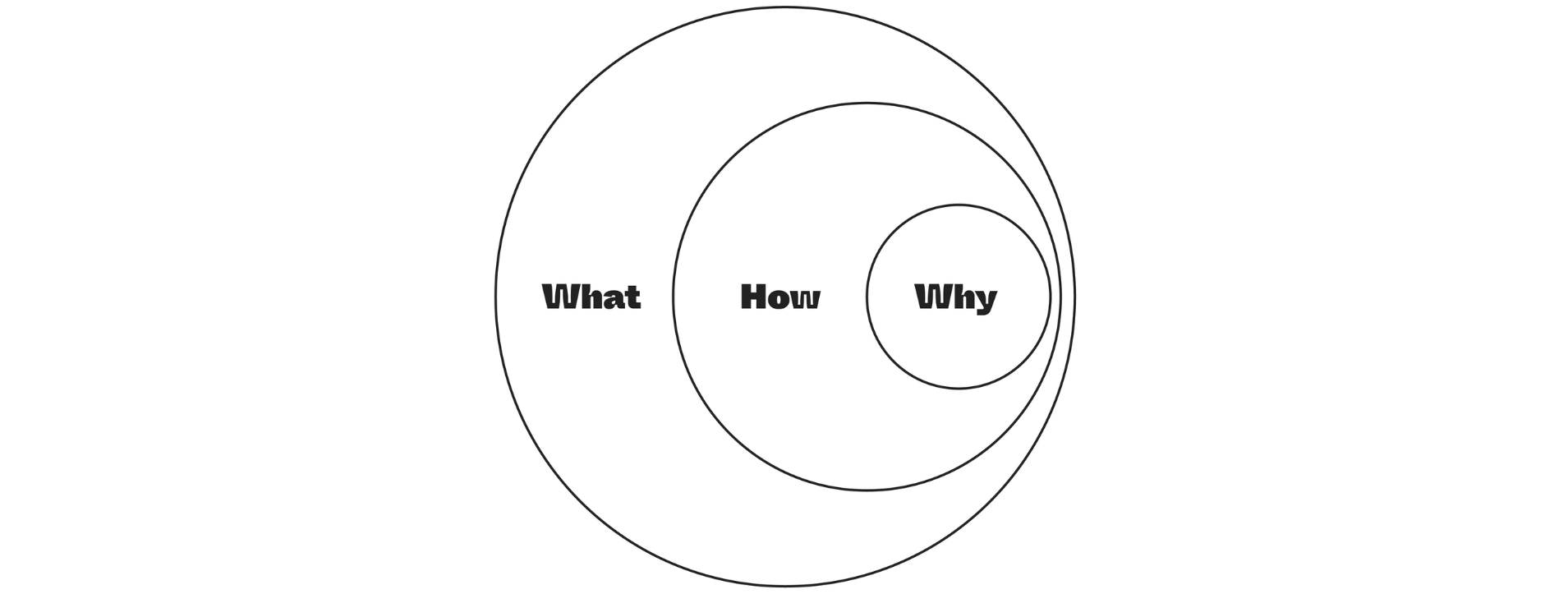

Which brings me to that other much debated cornerstone of contemporary marketing theory: Sinek’s golden circle. There's no doubt the ‘why/how/what’ trinity can help an organisation simplify a complicated story. There’s a reason this structure is also a commonly-used narrative device: ‘look-because-so’. It’s compelling and persuasive. Prominent Dutch listed companies like PostNL and Randstad, who use variants on the golden circle to present their annual reports, understand this principle only too well.

Nevertheless, critics of the approach point to the fact that companies that are renowned for their purpose-driven marketing, for example Patagonia, Ben & Jerry’s, Fermenich, Zappos and Ecover, are often more successful in the publicity they garner than they are in growing turnover or profit. Conversely, the world’s largest companies according to lists like Forbes Global 2000 and Fortune Global 500 tend to show at-best tepid enthusiasm for strategic transparency.

But to look at this solely through the lens of profit vs. purpose is to over-simplify the role the approach can play. As the foundation for tactics that will drive quarter-by-quarter expansion, the numbers may not stack up. But those companies that are prepared to commit to the long-term, consistent embodiment of a compelling brand story – not least the world’s most valuable company Apple, and more recently Oatley – have shown that the advocates of a golden circle approach are not living entirely in the world of fantasy.

In a post-digital world, where a brand is embodied as much by fleeting, ephemeral screen-based encounters as it is through storytelling, touch and feel, we can’t afford to be distracted by artificial, binary choices between art and science, the rational and emotional, myth and mathematics.

Successful brand building undoubtedly requires us to follow the science: mapping competitors, analysing sales data, understanding consumer behaviour. But the quality (and ultimately the viability) of that journey is ultimately determined by paying due deference to the art, too. Where data provides the substance of the story, character and plot make it meaningful.

But then I would say that… after all, I'm a Pisces.